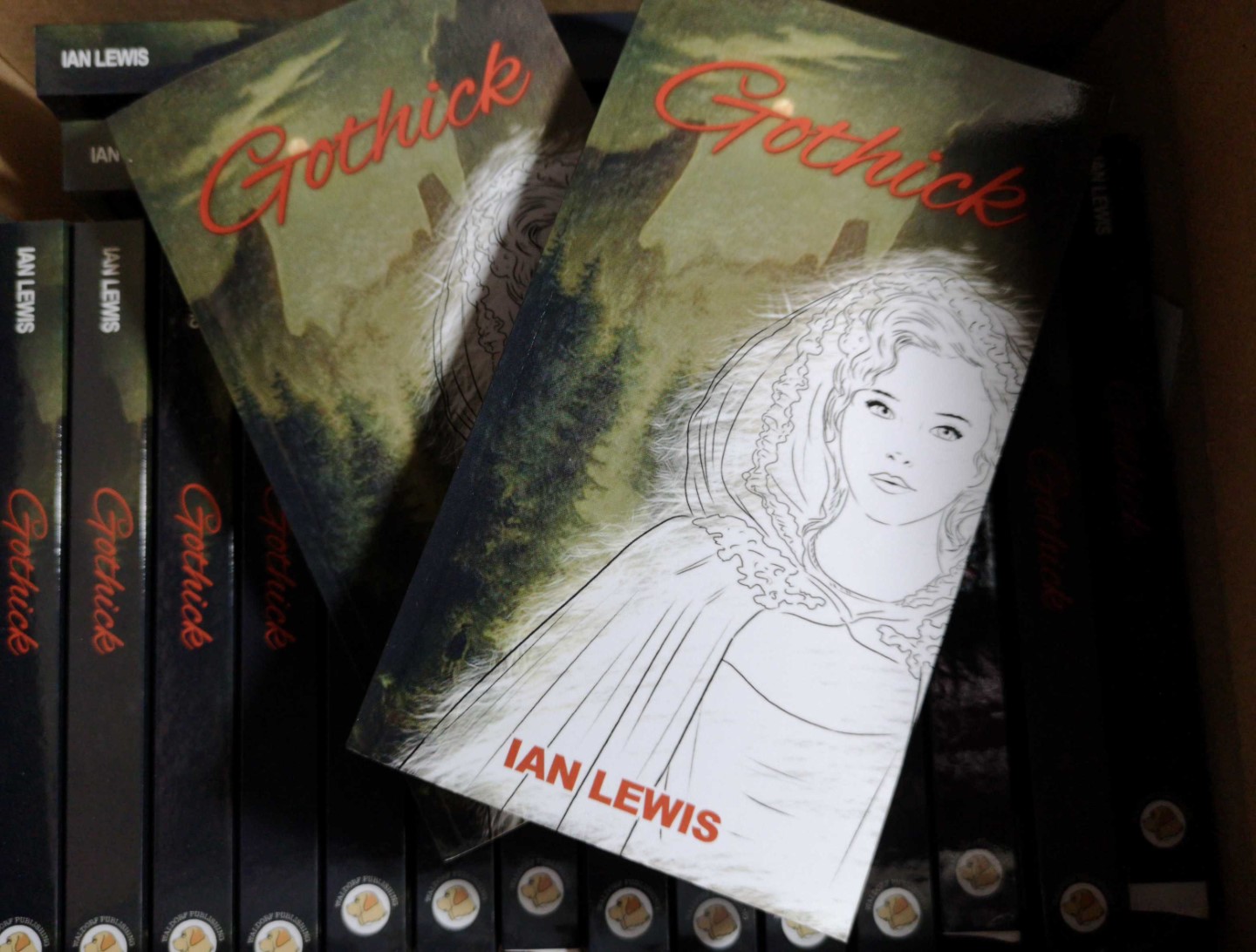

Gothick

I wanted to write a little more about my book, “Gothick”, which has just been published (January 2021). A bit of “behind the scenes”, if you like.

Why a historical novel?

For one reason or another – mainly simply enjoyment – I’ve read a lot of novels and diaries written in the years between, let’s say the American Revolution (or War of Independence, if you prefer) and the coming of the railways, say 1775 to 1825. I felt that I’d like to explore the time for myself – as a visitor, if you will.

The Gothick of the title (not a spelling mistake) refers to a tradition of romances popular in the late 1700s and early 1800s, which usually involved maidens in distress and ruined and/or gloomy castles in wild landscapes. Perhaps most famous of these are Horace Walpole’s Castle of Otranto and Ann Radcliffe’s Mysteries of Udolpho. But the initial inspiration for the book was Jane Austen, whose first full-length work, Northanger Abbey, makes fun of these gothick novels. Catherine, Austen’s heroine, sees mysteries and dark plots everywhere, but none of them are real. I also acknowledge a debt to Thomas Love Peacock, whose comic gothick novels Headlong Hall and Nightmare Abbey are echoed in the name of the General’s house.

I don’t see the past as a different universe. Superficially, our world is absolutely different from the world of two hundred years ago. Different from my own childhood, too. But people don’t change. Love, betrayal, anger, joy, friendship – people have felt and largely behaved the same for thousands of years, only the surroundings have changed. When she was a child in Vienna, my mother was looked after by a woman who had as a friend an old lady, who as a child had sat on the knee of Clemens Metternich, the architect of the 1815 Congress of Vienna and the post-Napoleonic peace process. That’s 200 years in a breath. These were people as real as your own memories of last year, not distant historical figures from the schoolroom.

So in the book, although, of course, most of the characters are fictional, I have involved some real people and the places they might have known.

The Hindoostane Coffee House was at 34 George Street, in central London, and the building still stands. It’s even still a restaurant – now (at the time I write this) Japanese. It was the first Indian Restaurant in Britain and was owned by Dean Mahomet, who appears in the book.

Less cheerfully, the Hangman William Brunskill was also a real person, as was his assistant, John Langley – who was indeed married with three children, though not much is known about either of them as people to spend time with.

The London coaching inns named and visited really existed, as did the George and Pelican Inn in Newbury (more often known as the Pelican, and – according to Samuel Johnson, who once stayed there – aptly named, from the size of its bill). The neighbouring Pelican Theatre was still standing in the 1970s, when it was finally demolished – though by then the building was used as a warehouse and hadn’t been a theatre for a very long time.

Most of this kind of detail comes from my familiarity with the time, and I hope it doesn’t appear as slabs of research, but as the everyday for the not so distant people of the story. I have been to 34 George Street. I have been inside the Pelican Theatre. As Lucy Worsley has said, we are separated from these people by time, but not space.